Travelling Solo in Lebanon

- Mandy Tay

- Sep 22, 2020

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 23, 2020

During a video call with my friends in Dubai, Chadi, a Lebanese, casually mentioned that he was going back to Beirut the next day, just 2 days after the explosion that ripped downtown Beirut apart. We couldn’t believe it. “Can you even get out of the airport?” Ghassan, another friend, asked in alarm. Chadi brushed it off, “Of course.” “But the roads will be full of destruction!” Ghassan implored. “There are other roads to take,” Chadi dismissed his urge with a nonchalant wave of his hand. “What if it rains? It will be dangerous with the chemicals still in the air,” another friend persisted. “It’s summer now, there will be no rain,” Chadi would not be swayed by our horror. “It’s common you know, one day it explodes and next day, khalas (“end” in Arabic). We are used to this,” Chadi shut us down with his acerbic humour, typical of the people I met from Lebanon.

First encounter with a Lebanese in Beirut and it was a young sculptor who asked me, "Are you happy?" When I said I was she smiled and replied that she was glad. "Many of us here are not but I am happy there are people in the world who are." It was only my first day in Beirut and I knew this would be an incredible trip that would hit me in all directions.

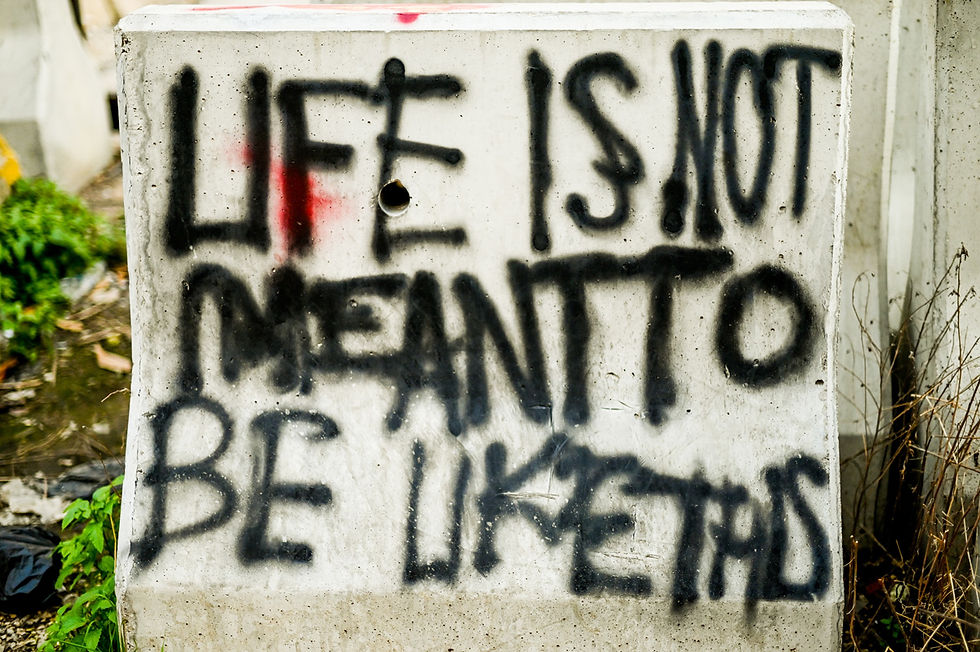

The Lebanese sense of humour is as dark as their history. It has to be. Ravaged by recents wars and struggling with political instability since late last year, the infamous brand of scathing sarcasm is their defensive mechanism. The only way to look at things, including daily atrocities like a 90% surge in the inflation rate of the Lebanese pound just last month, was to sharpen the blunt truth with piercing humour.

A graffiti on The Egg, an abandoned building in downtown Beirut.

On 4 August 2020 I woke up to terrible news of the blast in Beirut, a catastrophic result of the detonation of 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate that had been stored for six years without safety measures at Beirut's port. The hostel I stayed in January was now in shambles, a mere kilometre from the massive explosion that decimated downtown Beirut in seconds. The next few days, I watched the first filaments of fury flare up into an uncontrollable cauldron of public wrath, as thousands of angry Lebanese charged into Martyr’s Square, their eyes scorching with anger, demanding justice. Their unfiltered rage flowed from the city square to the screen of my phone, direct and live, posted on Instagram by friends in Lebanon.

The roaring waves crash against the rocks and a lone Lebanese in Tyre, a city built on ruins.

A small country with a population of 6.8 million, Lebanon has been struggling with an overwhelming 1.5 million refugees since the Syrian war crisis started in 2011, the highest per capita concentration of refugees in the world. Cornered by rising unemployment, soaring prices and a currency in free fall, Lebanon is further burdened by a pandemic and a deadly explosion which rendered 300,000 people homeless overnight. Refugees, who make up almost one quarter of the country’s population, are now offering their homes to newly displaced locals.

Visiting Souk al Ahad, one of Beirut's biggest flea market, was like walking through a dream, as patrons used their phone to light the wares on sale as the night closed in.

Tripoli, despite being the second largest city in Lebanon, was also the country’s poorest, with almost half living under the poverty line. And yet, this was where I met the most kindnesses. I must have been the only tourist they had seen for months and yet, instead of cornering me into buying souvenirs, they welcomed me gently and was eager to give me something, when they had barely anything. Peddlers offered me coffee and refused payment.

Tripoli was once known for its vast orange orchards and was on par with Beirut in terms of economic prowess.

Now it is on the verge of crumbling under poverty and unemployment.

On my way back to Beirut, I walked to the highway and hailed for a minibus to stop. The informal transportation system in Lebanon was at once strange and exhilarating. You would always find a way back even without planning. A taxi or a minibus would invariably come your way, honking for your attention. As I sat myself down in a packed minibus, I wondered if this would have an impact on your outlook in life. Chadi’s nonchalance suddenly made sense to me. Everything would work out. Surviving decades of strife and wars as recent as 2006 meant that you didn’t fuss over the details. Instead, time was better spent on the things that mattered.

Losing my bearings was the fastest way I found friends. On the way to Baalbek, two girls on the minibus made sure I got to my destination safely.

In December 2019 a good friend shared with me how her ex-colleague slipped into a sudden coma. It stopped me in my tracks. If there was something I wanted to do and I could manage it, what was I waiting for? This was how I decided to go to Lebanon on my own. I decided to live like the next year was my last. Just days before my flight, everyone tried to change my mind.

Lebanon was always on the top of my list. Hearing about the coma suffered by an acquaintance (he has since been on the road of recovery) was a timely wake up call. Here, a graffiti adorn the side of a building in Hamra, Beirut.

Don’t go, they said. The protests were in full swing. But I have heard so much about Lebanon when I was working in Dubai from 2011 to 2014. The electricity of its capital city Beirut, the quiet majesty of the Roman ruins in Baalbek and the smothering hugs from strangers I would meet. Yes, Lebanon did turn out to be dangerous. But only with its power to make anyone fall irrevocably in love with her. In fact, I wish I had been here earlier. Then again, I would have missed the best New Year’s Eve party I had ever had, right in the middle of a revolution.

A man scaling up the electric blue and pink streams of light while the cheers of “Sawra” (“revolution” in Lebanese Arabic) hung in the air on New Year's Eve.

On the night of 31 December 2019, a fellow traveller and I were trying to get to Martyr’s Square where there was a big New Year’s Eve party but we didn’t know how to say it in Arabic. I punched my fist into the air and yelled, “Sawra!”, (“revolution” in Lebanese Arabic). Martyr’s Square was where the nationwide wide protests started 2 months before. The taxi driver chuckled. He got it immediately. “Bravo!” he hollered approvingly, at my rare moment of clarity. It was the start of a magical night and I had hoped, by the end of it, a better year for Lebanon. The square was flooded with lights, music and camaraderie, an unusual moment of unadulterated joy in a tempestuous time. It was a night where sleep was forgotten and the revolution was put on hold.

A potent symbol of the revolution stands in the middle of Martyr's Square.

A few days later, I found myself soaked in the blinding rain a Lebanese winter often brings. A young Lebanese girl walking next to me on the road offered me shelter immediately. Under a sky stuffed with clouds heavy with rain, my profuse thanks stretched into a full conversation with this generous stranger. Before we parted, she even gifted me with a polaroid photo she took of the revolutions in the square.

I never felt unsafe in Lebanon. I roamed as far and as recklessly as I wished, almost tempting danger because there would always be a kind Lebanese who would come to my help. On a minibus, a beautiful woman next to me offered her Facebook contact and wrote me to check if I arrived to my hostel safely after we parted.

This was a country where even travellers took care of one another. Twice I had arrived in cities without knowing how to get back to Beirut. In Jounieh, two elderly ex-colleagues on a reunion sent me back while a group of young Europeans squeezed to make room for me in their rental car from Tyre, in the south of Lebanon back to bustling Beirut.

A seafaring town with a bustling harbour, a statue of Virgin Mary guards Tyre Harbour, much like how I was often looked after by both locals and fellow travellers alike.

I also remember fondly of the taxi driver who, instead of making a quick buck, encouraged me to walk down a highway to my destination 1km away. "Here?" I pointed to the 5 lanes of cars whizzing by me, inches away. I survived, partly because he was so sure I would. If my trip to Lebanon has taught me anything (besides crossing busy highways), it's that the Lebanese are fearless.

The impossible highway I had to cross, sometimes balancing myself on the kerb while cars sped past me.

"You can do it!"

A taxi driver I approached gave me the courage to attempt the seemingly insane feat.

Just before I left Lebanon in January, I met a Syrian-Ukrainian modern dancer who used to be a gymnast. I often collaborate with dancers when I travel and she was introduced to me at a chance meeting in a cafe that has since been destroyed by the explosion. “What if you danced, for a person you might never see again?” Dana laughed and so did I. “Is it too early for such drama?” I asked. It was a cold winter morning in January 2020 and we met at 8am to have the whole space to ourselves. The space was The Egg, a cinema which was built in 1965 but was never finished because of the Lebanese civil war which lasted for 15 years between 1975 to 1990. “No,” she said. “It’s too close to my heart.” 7 months later, we had no idea how much harder this would hit home.

A Beiruti landmark, The Egg is an abandoned building which was taken over by protestors in October 2019.

Dana Amer, a young Ukranian-Syrian dancer leaps across the graffiti lined across the interior of The Egg. It was a cold winter morning and she poured her heart out in the dance video that we shot together.

Just around the corner from The Egg was the abandoned Grand Theatre des Mille et Une Nuits (Grand Theatre of 1001 Nights). And the dancer introduced to me for this shoot was named Sherazade. Some dreams are indeed too good to be true. Video of the dance here.

In another dome, 2 hours away from Beirut, is the Rachid Karami International Fair in Tripoli, designed by the revolutionary Oscar Niemeyer. The acoustics in the cavern was extraordinary. Every scratch of my shoe on the steps echoed like a muffled roar in a dream which seemed to go on forever. Just like the nightmare Lebanon is trying to wake up from.

Tripoli's futuristic fairground, designed by Brazilian modernist Oscar Niemeyer,

stands unfinished and forgotten, next to the city's 14th century mosques.

In the 10,000 hectare site lies a dome with incredible acoustics, like a resounding roar of the ambitious and unfulfilled dream that is the fairground itself.

I didn't realise this but when I went to Lebanon (Dec 19 - Jan 20), it was an incredibly small window of opportunity to visit the last country I wanted to see (bookended by revolutions which started in October and Covid19).

Some scenes I had not expected to see when I arrived in Beirut. One of them was the view of Jounieh dipped in golden hues at sunset. It was quite a climb to reach this breathtaking viewpoint and I was half panting, half gasping as the violent winds whipped my hair around my face.

Byblos, just an hour away from Beirut, has been continuously inhabited since 5000 BC, making it one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.

Bolted in our own atmosphere of thwarted hopes for most of 2020, it will be a while before the skies clear up. Use that gift soap and light that artisanal candle you have been saving up for so long. When our doors are unlatched again, take that trip you’ve always wanted, before it’s too late.

Some trips stay with you forever. Pictured: An abandoned building framed by crimson leaves in downtown Beirut.

Text and photos by Mandy Tay

Comments